01 Nov Green Home Costs, Challenges Add Up

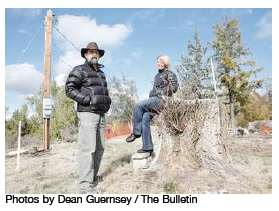

But Bend couple is not giving up on building extremely green home

By Kate Ramsayer / The Bulletin Published: November 01. 2010 4:00AM PST

Editor’s note: Tom Elliott and Barbara Scott invited The Bulletin to follow their green-building project from start to finish to share their goals, decisions, costs, concerns, problems and achievements, and to be an open book on what it takes to build such a home. The Bulletin is following the couple’s project through periodic stories. In this installment, Elliott and Scott share how much they’ve spent before even beginning construction — and the challenges they’re facing trying to build a home that meets the strict requirements of the Living Building Challenge.

Editor’s note: Tom Elliott and Barbara Scott invited The Bulletin to follow their green-building project from start to finish to share their goals, decisions, costs, concerns, problems and achievements, and to be an open book on what it takes to build such a home. The Bulletin is following the couple’s project through periodic stories. In this installment, Elliott and Scott share how much they’ve spent before even beginning construction — and the challenges they’re facing trying to build a home that meets the strict requirements of the Living Building Challenge.

The groundbreaking for Barbara Scott and Tom Elliott’s new home, designed as a model of energy efficiency and green living, was originally slated for July. But it was pushed back to August, Scott said, then September.

Now, the couple hopes to start work on the 3,000-square-foot home by Christmas.

The delays involved with building a home using only Earth-friendly materials, designing a system to catch rainwater to supply the household’s use and more have been discouraging. The couple questioned whether to proceed with the strict green standards. And the costs — which have reached $270,000 before the first concrete is poured or a nail pounded — have far exceeded expectations.

“There was a point where I was saying this is ridiculously expensive,” Scott said.

But now, Scott said, she and Elliott are rejuvenated. They decided to continue with green-building programs, including the Living Building Challenge. Among its long list of requirements are strict guidelines for building materials, and mandates for on-site electricity production, and water collection and treatment.

Only one house has been built and tested in North America under Living Building Challenge criteria, and that residence only met two-thirds of the program’s standards.

“This is our cause, this is our passion right now,” Scott said.

The goal, the couple said, is not only to build a house for themselves, but to get the research and legwork done so others can more easily incorporate different green elements in future projects.

“We’ve paid for a lot of things other people won’t have to,” Elliott said.

The project team is keeping track of the different materials, he said, and plans to share them with others — either for free or for a subscription fee designed to recoup some of the money spent researching the options. So far, the team has spent more than $34,000 researching how the project can meet Living Building Challenge and Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design certifications.

The project team is keeping track of the different materials, he said, and plans to share them with others — either for free or for a subscription fee designed to recoup some of the money spent researching the options. So far, the team has spent more than $34,000 researching how the project can meet Living Building Challenge and Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design certifications.

The project also is a way to re-examine how people build houses, he said. When it takes so much effort to find nontoxic materials, Elliott said, it makes him question what people are exposed to each day.

“Sometimes it’s the extremes you have to go to, to point out the insanity,” Elliott said, talking about the potentially hazardous materials people live with every day in an average home.

And going to those extremes can cause things to take longer than expected.

“The biggest challenge is going into the unknown, with a brandnew program,” said Al Tozer, owner of Tozer Design Studio and the project’s lead designer.

So far, the Living Building Challenge has only certified two commercial buildings and the one residence, which is located in British Columbia.

Finding the right materials

The building materials category continues to cause delays and challenges for the Bend team.

Living Building participants have to research every material used in construction, from beams to flooring to faucets, and ensure they don’t contain any ingredients on the Living Building’s “red list,” which could harm the environment or residents’ health. The Living Building Challenge also sets limits on where the materials can come from, to emphasize buying locally and to reduce the impacts associated with transporting products long distances.

For example, the project is limited to Forest Stewardship Council-certified wood and wood products, Tozer said. That’s simple enough for some uses, since the Warm Springs mill produces lumber that qualifies.

But architectural plans usually involve engineered lumber made of wood pieces glued together, which is both light and strong.

Tozer can’t find any Forest Stewardship Council-approved versions of that engineered lumber.

So the designers have to go through the whole house and adjust areas where they would normally use the engineered wood, putting in additional support or substituting different products.

“Instead, we have to use real wood, and we have to ask (the wood) to do things that oftentimes we don’t ask it to do,” he said.

“We’re not only finding the materials, we’re designing around the materials. So that definitely takes more time.”

In some cases, it takes time because the designers are working with the Living Building Challenge to determine which materials are acceptable.

For instance, the team wants to use a type of plaster called American Clay for the interior walls — but it comes from too far away, according to Living Building Challenge standards, Tozer said.

But the team is working with the Living Building Challenge staff in Seattle to prove the material has other benefits that cannot be found locally, and should be an acceptable option.

“It’s not just picking a material,” Tozer said. “We need to prove its worthiness to the Living Building Challenge administration.”

‘Much more complicated’

Most residential projects have their ups and downs in the design phase, said M.L. Vidas, owner of Sustainable Design Services of Bend and the team’s sustainability consultant. Elliott and Scott’s house is like others, she said.

“This looks like it’s just a house, it’s going to have walls and a roof, and windows and doors and rooms,” Vidas said. “But it is so different … it is much more complicated than it first appears — and complex.”

Designing the roof for a typical house, for example, involves asking a number of questions, she said, like whether the roofing material works, whether the owners can afford it, and whether they like its appearance.

But add in the Living Building Challenge, and the list of questions grows, Vidas said. Because all the rainwater will be collected for household use, planners have to verify it’s safe to drink water that flows off roofing material. And the material has to be local, as well as Earth-friendly.

The implications of each decision have to be considered, she said.

For instance, Elliott and Scott plan to store all of their water in a cistern — but sometimes, if water is stored for too long, it can taste funny, even if it meets all health standards, Vidas said. One option would be to install pumps to circulate and aerate the water — but that takes energy, which is in short supply since the house is designed to run solely on solar and wind power.

“If we make that decision without thinking about the consequences on the energy side … all of a sudden, you’ve blown your energy budget without even being conscious of it,” Vidas said.

But it’s good to know that other projects have met the Living Building Challenge standards, she said, even if the number is still small.

“It’s inspiring knowing other teams have succeeded,” she said. “It’s not impossible.”

Kate Ramsayer can be reached at 541-617-7811 or at xenzfnlre@oraqohyyrgva.pbz.